[Patient’s Voice] Ms. Sachiko Ito – Non-Tuberculosis Mycobacterial Lung Disease (March 18, 2022)

- Home >

- Information >

- News >

- [Patient's Voice] Ms. Sachiko Ito - Non-Tuberculosis Mycobacterial Lung Disease (March 18, 2022)

I hope more healthcare professionals take an interest in Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) and work to promote the appropriate usage of antimicrobials.

Ms. Sachiko Ito

Supporter, AMR Alliance Japan

Person Affected by Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial (NTM) Lung Disease

Contents:

(1) Developing Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease and the painful first six years of pharmaceutical therapy

2004 to 2009: Onset, exacerbation, and starting treatment

2009 to 2010: Attempting multidrug therapy, trouble with side effects, and transferring hospitals

(2) Worry over the lack of improvement of symptoms and losing trust in healthcare

2011 to 2015: Further trouble due to lack of improvement of symptoms and developing distrust toward healthcare

2015: Hemoptysis and transferring hospitals

(3) Finally finding a treatment and days of constant struggle with repeated microbial substitution

2016 to 2017: Discovering clarithromycin monotherapy resistance, starting multidrug therapy

Afterwards: Testing negative for AMR bacteria, experiencing microbial substitution twice, and today

(4) Living with treatment and future expectations for healthcare professionals

Treatment Record for Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial (NTM) Lung Disease

(1) Developing Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial (NTM) lung disease and the painful first six years of pharmaceutical therapy

2004 to 2009: Onset, exacerbation, and starting treatment

In 2004, when I was 39, I underwent my annual medical examination like usual. Rather than getting a notification of my results in the mail like always, I received a phone call several days later. They said I required a more detailed examination. I went to the hospital immediately. There, the doctor told me, “It’s not lung cancer, but there’s a chance you have non-tuberculous mycobacterial lung disease.” I had never heard of any such disease before, and was confused. I grew worried because, at the time, I was told that prognosis was poor and that there was no medicine that could cure it. Day after day, I did research online, but there was not much information available.

At the same time, I underwent a bronchoscopy and other tests performed at Hospital A and tested positive for Mycobacterium avium (Gaffky scale VIII). Based on those findings, I was diagnosed with pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). It was 2005 at the time, and because I was not experiencing any noticeable symptoms, I was placed under further observation. In my case, that meant having X-rays, sputum tests, and blood tests taken periodically.

In 2007, when I was 42, I got sick and had difficulty breathing due to a severe cough and phlegm. I went to see a doctor outside of my normal appointment and began taking 400 mg of an antimicrobial called clarithromycin once per day. It caused continuous nausea and diarrhea, so I was also prescribed a bowel regulator and an anti-nausea medication. Seven months later, in February 2008, although I still had some coughing and phlegm, I was told that I would be stopping clarithromycin because my X-ray showed it had been effective. However, my joy over stopping clarithromycin was short-lived. At a follow-up visit five months later, I was told my condition had worsened by several years’ worth of progression in only a matter of months. So, I was prescribed clarithromycin once again. Six months later, I was told that the treatment was not showing any effect and that my dosage was being doubled to 800 mg per day. The increased dose also caused me to have a bitter taste in my mouth. More than anything, I began feeling more doubtful toward the decision to restart clarithromycin with an increased dosage.

2009 to 2010: Attempting multidrug therapy, trouble with side effects, and transferring hospitals

In March 2009, I underwent various tests at University Hospital B, where I was referred to when my attending physician at Hospital A left their position. As a result of those tests, I was told my condition was getting worse and that it was crucial that I begin triple-drug therapy with clarithromycin, rifampicin, and ethambutol. I had also heard about the side effects of those medications and was unsure what to do. After consulting my family, I decided to start triple-drug therapy in July 2009. However, by the third week of treatment, I was experiencing chills, fever, and fatigue so strong I could not even get out of bed. During a consultation the following month, the doctor said, “Triple-drug therapy is absolutely necessary, but for the time being, we will switch you to an alternative and see how you respond.” The triple-drug therapy was discontinued. After a CT scan performed in May 2010, I was told that although my existing lung cavity had shrunk, a new one had formed. I was told, “You should continue triple-drug therapy. If you don’t want to, you will have to come in twice a week for intramuscular injections.” I was left with the impression that university hospitals force people endure painful, intense treatments. I thought they would not be understanding toward the fact that I had to work for a living, so I canceled my appointments at the university hospital and went to my previous attending physician, now at Hospital C. At Hospital C, they said, “You don’t have to continue triple-drug therapy if it is too hard on you, because there are strong side effects and there is no guarantee that it will make you well. Let’s focus on clarithromycin and add carbocisteine.” Feeling reassured, I decided to trust them.

(2) Worry over the lack of improvement of symptoms and losing trust in healthcare

2011 to 2015: Further trouble due to lack of improvement of symptoms, and developing distrust toward healthcare

In March 2011, my attending physician left their position again and I was placed under a new one, but my treatment regimen with clarithromycin and carbocisteine went unchanged. After that, when I told the doctor about any symptoms I was feeling, they said, “That isn’t a sign of your pulmonary MAC getting worse. Your X-rays are the same as before.” With that, I no longer had anything of my own to report. Although I was given blood tests, I did not take any sputum tests or CT scans, so I was just visiting the hospital regularly to receive my medications. However, four years after resuming monotherapy, in July 2014, I began experiencing a severe cough with phlegm. Visiting the doctor, I was told I might have a bacterial infection, and was prescribed sultamicillin tosilate hydrate. We later discovered I was infected with Haemophilus influenzae, and my symptoms improved with treatment. By then, ten years had passed since my first examination. Although it was clear my subjective symptoms were getting worse, my treatment was not progressing and I grew more unsure toward my attending physician. I requested to be transferred to a special hospital and was told, “If you transfer to a special hospital, you will be given strong medication and have side effects again. You should think it over carefully.” This made me reluctant to transfer. Due to this and other events, like one of my family members having a surgery, I put the transfer on hold.

2015: Hemoptysis and transferring hospitals

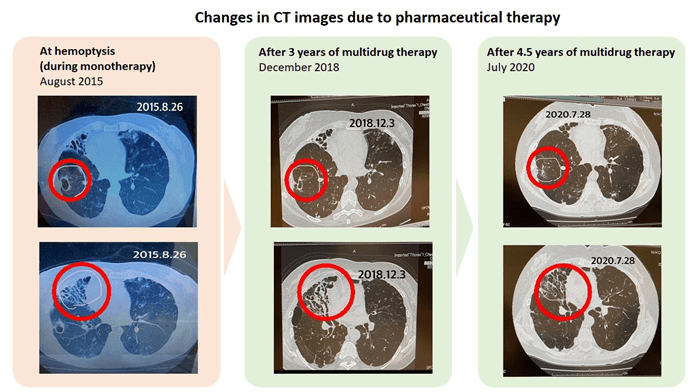

In August 2015, while continuing clarithromycin monotherapy at Hospital C, I had hemoptysis for the first time. My doctor told me, “I’m not seeing signs that your pulmonary MAC lung disease is growing worse. The hemoptysis was probably caused by a blood vessel that burst due to the burden placed on your bronchial tubes when you picked up something heavy.” I was advised to rest for two weeks. Later that year, in October, I attended an open lecture at a hospital specializing in pulmonary NTM disease. I consulted the lecturer, who said, “There is a risk of developing resistant bacteria with your current medication. In your current condition, it is worth taking the medications (you stopped before). You might be able to take them if you undergo desensitization therapy and are careful about side effects.” I decided to transfer hospitals.

When I told my attending physician about my decision, they said, “I don’t mind writing you a referral, but I think the specialist will be angry with me because I heard clarithromycin monotherapy should be avoided.” Learning that I had been under clarithromycin monotherapy for such a long period when the doctor knew that it was supposed to be avoided left me speechless. At that moment, I realized that stopping treatment at the university hospital on my own accord had been a mistake.

(3) Finally finding a treatment and days of constant struggle with repeated microbial substitution

2016 to 2017: Discovering clarithromycin monotherapy resistance, starting multidrug therapy

I then transferred to Hospital D, a special hospital, where they performed a sputum test that found clarithromycin-resistant Mycobacterium avium. My treatment with clarithromycin was discontinued and I was admitted for desensitization therapy. With antiallergics, I was able to begin multidrug therapy with rifampicin and ethambutol. For the next two years, I was able to continue that regimen while feeling well in my everyday life.

Afterwards: Testing negative for AMR bacteria, experiencing microbial substitution twice, and today

After continuing multidrug therapy at the special hospital for three years, I finally tested negative for clarithromycin-resistant MAC bacteria, something we had considered difficult.

However, even seventeen years after my initial diagnosis, I have yet to complete treatment. This is because I was infected with the same non-tuberculous Mycobacterium abscessus subspecies massiliense and underwent new treatment, and even when I tested negative for that, I was infected with Mycobacterium avium.

We have found that the strain of Mycobacterium avium I am currently infected with is susceptible to clarithromycin, so I am now receiving ongoing triple-drug therapy with clarithromycin, rifampicin, and ethambutol.

When I wonder why microbial substitution keeps occurring like this, and I get infected again and again, it makes me sad. I started lightly cleaning the shower and bathtub after every use and leaving the heavy cleaning to my husband. I quit gardening and had our plumbing renovated. Even after all that, I keep getting infected. Every time, I wonder, “Why does this keep happening?” But now that it has happened again, I have no choice but to get treatment for the new bacteria.

That is because I have no intention to stop receiving the treatment I need to stay alive.

(4) Living with treatment and future expectations for healthcare professionals

The difficulties I feel as a patient are rooted in the fact I was in a constant state of anxiety because even with guidelines, there were no clear indicators for recovery or how much time recovery would take. There have been many things I did not know without trying, like whether I should take a medicine or not, how the side effects would be, or if the medication would even work if I continued taking it. Furthermore, there were many elements that caused me to worry or that I did not understand, like the fact that there are even some doctors who are reluctant about certain treatments. These were all obstacles that made me hesitant to get involved in my treatment as a patient.

One unique characteristic of NTM treatment is that even if you are lucky enough to be able to take the medication and eventually test negative, you still have to continue taking the medication for about a year. During that time, you worry about which bacteria you will test positive for next. I felt like I was moving a piece around on an endlessly looping board game.

In addition to the burden on your body and the heavy psychological load, taking large amounts of medication for years on end comes with high financial costs, as well. That is why you are normally happy when you are told you can stop taking something. However, for NTM patients, those words are like a dream. At the same time, they can also become a source of fear – you grow uncertain and worry that you might test positive again, and have to go back to square one. I would like for every healthcare professional to understand the anxiety and complex mixed feelings of patients. I think I will have to continue facing this disease for a long time to come, but other patients and I can give each other the encouragement we need to hang in there day by day, until a cure is available. I would be happy if you could please understand our disease and give us your encouragement. I look forward to your support.

Case study 01

Dr. Keiji Okinaka (Director of Infection Control and Prevention Section, National Cancer Center Hospital East / Department of General Internal Medicine, National Cancer Center Hospital East /Division of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, National Cancer Center Hospital)

“A disseminated filamentous fungal infection that broke through echinocandin antifungal treatment”