[Event Report] The 49th Special Breakfast Meeting – Push and Pull Incentives to Address AMR: The Experience of CARB-X and the potential for Public-Private Partnerships in Global Health (September 21, 2022)

- Home >

- Information >

- Event >

- [Event Report] The 49th Special Breakfast Meeting - Push and Pull Incentives to Address AMR: The Experience of CARB-X and the potential for Public-Private Partnerships in Global Health (September 21, 2022)

For the 49th Special Breakfast Meeting, we hosted Professor Kevin Outterson (Executive Director, CARB-X). Based on his experiences as the Executive Director of CARB-X and Professor of Law at Boston University, Professor Outterson outlined the next steps for combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and promoting antimicrobial R&D, and discussed the potential for the Japanese government to establish impactful policies that will incentivize action in this area.

To prevent the potential spread of COVID-19 at this Special Breakfast Meeting, the venue was thoroughly disinfected, the flow of people at the venue was controlled, and guest capacity was limited.

Key points of the lecture

- Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an urgent health threat. AMR was the direct cause of 1.27 million global deaths in 2019, which is higher than the number of deaths from HIV/AIDs and malaria.

- When effective antimicrobials are unavailable, not only does the number of deaths due to infectious disease increase, it also becomes impossible to provide standard medical treatments. This results in an overall weakening of the healthcare system. In this context, AMR is not only a problem that is related to infectious disease. Rather, it should also be taken as a problem facing Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the global health architecture because AMR has relatively few global health institutional resources relative to the size of the problem.

- CARB-X is the world’s largest public-private partnership on AMR which focuses on accelerating R&D projects in early stages of development, from hit to lead to Phase I clinical trials. It aims to promote R&D on innovative preventatives, diagnostics, and therapeutics for infectious diseases caused by the most dangerous drug-resistant bacteria.

- To enable the long-term use of antimicrobials in a sustainable environment, push incentives that support R&D must be further reinforced. Japan should expand investments in the R&D pipeline, especially for the preclinical stages, and joining CARB-X will help make that possible. Japan already invests in AMED (pre-CARB-X) and GARDP (post-CARB-X). Furthermore, Japanese pharmaceutical companies have contributed to the AMR Action Fund (post-CARB-X). CARB-X is complementary to these initiatives, and much needed to ensure that AMED projects have a future towards the clinic, and that GARDP and the AMR Action Fund have enough high-quality, high-impact projects to work with.

- While reinforcing push incentives, another crucial step will be establishing pull incentives that support the commercial launch of antimicrobials after regulatory approval by delinking usage/sales volumes and revenue. Creating pull incentives will complement push incentives and the drug discovery ecosystem and make it possible to overcome the structural challenges in the market.

The current state of AMR – A significant burden and growing threat

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an urgent health threat. According to a 2022 study known as the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance (GRAM) report, AMR was the direct cause of 1.27 million global deaths in 2019, which is higher than the deaths caused by HIV/AIDs and malaria. This number increases even further to 4.95 million deaths when deaths associated with AMR are included.

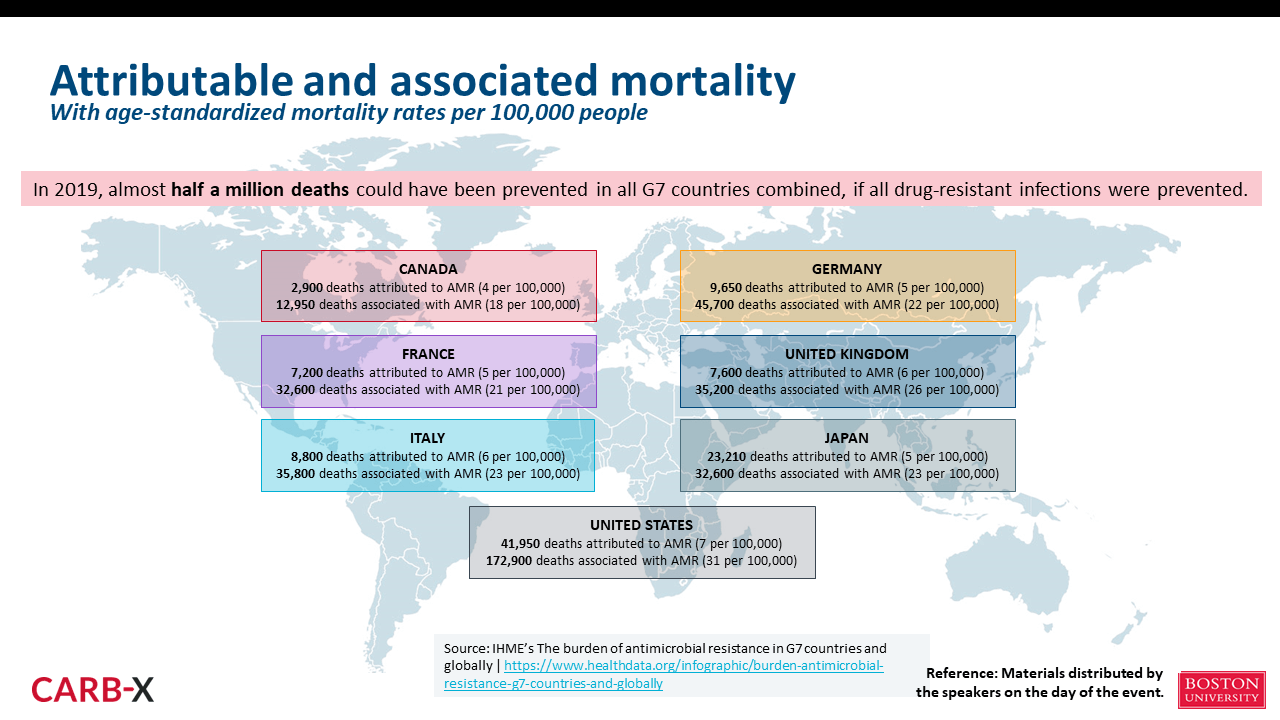

The number of deaths due to AMR is projected to increase to 10 million by 2050, the majority of which are expected to occur in Asia and Africa. At the same time, there are already many deaths attributed to or associated with AMR in each G7 country. If appropriate measures to combat AMR had been in place in 2019, it is likely that almost 500,000 deaths could have been prevented in all G7 countries combined (Figure 1). It is safe to say that AMR is a global issue that affects both developed and developing countries.

However, AMR is not only a problem related to infectious disease; it can also be taken as an issue that affects Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the global health architecture. Infectious disease is the second leading cause of death among people who are immunocompromised, and antimicrobials are essential for the 10 million people around the world who undergo cancer treatment each year and have suppressed immune systems. In addition, to prevent surgical site infections and other complications, antimicrobials are often administered after surgical procedures. Globally, approximately 20% of births are by cesarean section, which is a surgical procedure and also tends to require the use of antimicrobials. Antimicrobials are also important for preventing opportunistic infections in people with chronic diseases with weakened immune systems due to the side effects of their treatments. In other words, a lack of effective antimicrobials will not only lead to more deaths due to infectious disease; it will also prevent standard healthcare from being delivered and ultimately weaken healthcare systems overall.

Despite our great need for antimicrobials, there has been a drought in innovation for antimicrobials. Scientifically, it is difficult to conduct R&D for pharmaceuticals with novel mechanisms of action. Even if pharmaceuticals that overcome those scientific difficulties are developed, economic uncertainties in the antimicrobial market create high hurdles to commercial launch. Over the past decade, 18 antimicrobials have been approved in 15 high-income countries including G7 members, but only five of those antimicrobials have been launched and marketed in Japan. Scientific problems in antimicrobial R&D and the dire economic situation in the antimicrobial market are hindering access and preventing these pharmaceuticals from reaching the people who need them.

The role of CARB-X in global AMR control and antimicrobial R&D

The Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) is the world’s largest public-private partnership for promoting early-stage R&D on innovative preventatives, diagnostics, and therapeutics for infectious diseases caused by AMR. CARB-X is supported by the Wellcome Trust, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and from national governments in countries like the U.S., the U.K., and Germany. Since its establishment in 2016, CARB-X has committed approximately $400 million to antimicrobial R&D and related activities. It is my sincere hope that Japan also joins this effort to support global antimicrobial R&D.

CARB-X supports a broad range of R&D initiatives in three areas: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Including projects that were ongoing as of September 2022, CARB-X has provided support for a total 92 projects to date. CARB-X places heavy emphasis on supporting therapeutics. It prioritizes innovative products, such as those that utilize new mechanisms, as well as products that target diseases with high mortality rates rather than those with high prevalence. Many projects supported by CARB-X are related to diseases with high mortality rates, like lower respiratory infections (LRI) and bloodstream infections (BSI).

However, the road to commercial launch is long. To meet our objective of obtaining approval for six new therapeutics per decade, 200 preclinical developments must be made and 30 projects must begin First-in-Human studies every ten years. To help achieve these goals, CARB-X is accelerating projects in preclinical research and early clinical development, from hit to lead to Phase I clinical trials. To ensure antimicrobials are sustainable, in addition to R&D or innovation, we are also focusing on two other points: access to the products that reach the market, and appropriate use or stewardship. To help improve antimicrobial access and stewardship in low-income countries, in March 2021, we created a manual for companies leading R&D for new antimicrobials called the “Stewardship & Access Plan (SAP) Development Guide.”

Collaborating with CARB-X to promote Japan’s antimicrobial R&D and AMR countermeasures

Japan is a global leader in initiatives in the field of global health. In particular, Japan has made significant contributions to efforts for UHC and Global Health Security (GHS), as well as to R&D through programs like the GHIT Fund. AMR has also been included as a high-priority policy issue in various documents from the Government of Japan. Specifically, AMR has been prioritized in the Pharma Industry Vision 2021, the FY2022 MHLW science research program, the new Global Health Strategy, the Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2022, and the Grand Design and Action Plan for the New Capitalism.

As mentioned above, a lack of effective antimicrobials not only means more deaths from infectious diseases; it also weakens entire healthcare systems directly because standard treatments can no longer be provided. This is precisely the reason AMR should not be seen as an issue that is limited to infectious diseases, but as one that also threatens UHC and the global health architecture. Based on a recognition of these facts, it is highly significant for Japan to serve as a leader in measures to combat emerging and reemerging infectious diseases, including AMR.

Many antimicrobials which are used as standard drugs globally (e.g., meropenem, doripenem, colistin, delamanid) were developed in Japan, and Japan can further expand its capacities and expertise in AMR R&D. As a matter of fact, according to an AMR pipeline analysis from WHO, Japan ranks fourth to sixth in the world in terms of the number of institutions with preclinical antimicrobial projects.

However, fewer than 1% of all Expressions of Interest (EOI) submitted to CARB-X have been from Japan. CARB-X has started new funding rounds, so it is my sincere hope that Japan will submit more applications in the future.

As it appears that Japan is experiencing issues related to funding, particularly during Phase I and after approval, push incentives that support R&D must be further reinforced in Japan. Support from CARB-X is strong from early phases of development from hit to lead to Phase I clinical trials and I would like for that support to be utilized to complement R&D in Japan. CARB-X would also like to fully support commercial launch for research projects already supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED). All stages of R&D and post-approval require sufficient funding, but gaps in funding not only impact how many antimicrobials are approved, they can also hinder antimicrobial access. In addition to commercial launch, we also want to contribute to improving global access to antimicrobials.

As stated in the Government of Japan’s National Action Plan on AMR, not only will it be important to conduct R&D for AMR control, it will also be important to collaborate in a manner that surpasses the boundaries of nations and organizations. The Health Ministers’ Communiqué presented at the 2022 G7 Elmau Summit in Germany emphasized the importance of supporting organizations and initiatives like CARB-X, the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), and SECURE. CARB-X also wants to share knowledge, skills, and resources obtained through public-private partnerships in order to achieve the goals outlined in that Communiqué. I am certain there will be synergies between Japan and CARB-X in conducting R&D, collaborating with G7 countries, promoting leadership from Japan in the Asia-Pacific region, and advancing the National Action Plan on AMR.

The structural issues of the antimicrobial market and the pull incentives needed in Japan and abroad

The economic situation in the antimicrobial market is dire. Even companies with new candidates in Phase III clinical trials or that have already been approved are struggling to stay in business. Over the past ten years, median antimicrobial sales in the U.S. were only $16.2 million. Since 2010, many companies have failed, and investors have already lost over $3.5 billion.

Overcoming the structural challenges of the antimicrobial market and achieving sustainable innovation and stewardship will require new business models that utilize pull incentives. Pull incentives are mechanisms for delinking the antimicrobial usage or sales volumes from revenue, and two models for doing so have been envisioned based on the degree of delinkage. The first is the subscription model, in which purchases are made over a fixed period. In the subscription model, governments would regularly purchase new antimicrobials for up to 10 years to fully delink usage or sales volume and revenue. Regarding the amount we would need to invest to achieve a fully delinked model, the best estimate for a global antibacterial subscription is $3.1B per drug over ten years. The Japanese “fair share” of this amount is an average of US$30 million per drug per year, or about US$90 million per year for pull incentives (assuming 3 drugs at any given time). The other model is a revenue guarantee at the same fair share target, but with some of the revenues coming from market sales and the balance covered by the government. In this model, governments would cover the minimum annual revenue for antimicrobials, but because companies could also earn revenue from normal operations, usage or sales volume and revenue would not be fully delinked. The best estimate for the direct government contribution to a global partially delinked program is $1.6B per drug over ten years. Although the investment for the revenue guarantee model appears smaller, looking at the entire picture, the costs of antimicrobials used in normal medical care would be an additional burden for society to bear because companies would continue normal business operations. Either of these pull incentives would build a new globally relevant institution within global health architecture and will support UHC by ensuring that antibiotics remain effective.

For push incentives, if Japan contributed to CARB-X at a level similar to a country with a similarly-sized economy such as Germany, the annual contribution would be US$10 million. Hence the additional investment from Japan to fully respond to the need for R&D would be approximately US$100 million, with 90% of that going to pull incentives and 10% to CARB-X. No estimate is made here of the needs relating to GARDP and SECURE.

The U.K. has introduced a subscription model on a trial basis while Sweden has introduced the minimum revenue guarantee model. Although each model has a different degree of delinkage, we can assume the differences are negligible when market sales are small. Instead, what is important when introducing pull incentives is to assess the social value delivered in terms of meeting unmet medical needs while still supporting access and stewardship. Models should be implemented in a manner that harmonizes with each country’s health insurance or reimbursement systems while focusing on if those models will be sustainable for several decades or more. Each country should demonstrate leadership when considering which model to adopt and how to implement it within its own systems. Creating pull incentives will complement push incentives and drug discovery ecosystems and make it possible to overcome the structural challenges of the antimicrobial market.

(Photographed by: Kazunori Izawa)

■Speaker Profile

Professor Kevin Outterson (Executive Director, CARB-X)

Professor Kevin Outterson is a global thought leader on business models for antibiotic development and use. He is Professor of Law and N. Neil Pike Scholar of Health and Disability Law at Boston University School of Law, where he leads multi-disciplinary teams to solve global health issues. He is the Executive Director and Principal Investigator of CARB-X, which provides funding to accelerate research for developing antimicrobials and diagnostic methods for infections caused by AMR bacteria. He is also a partner in DRIVE-AB, a multinational public-private research project funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI).